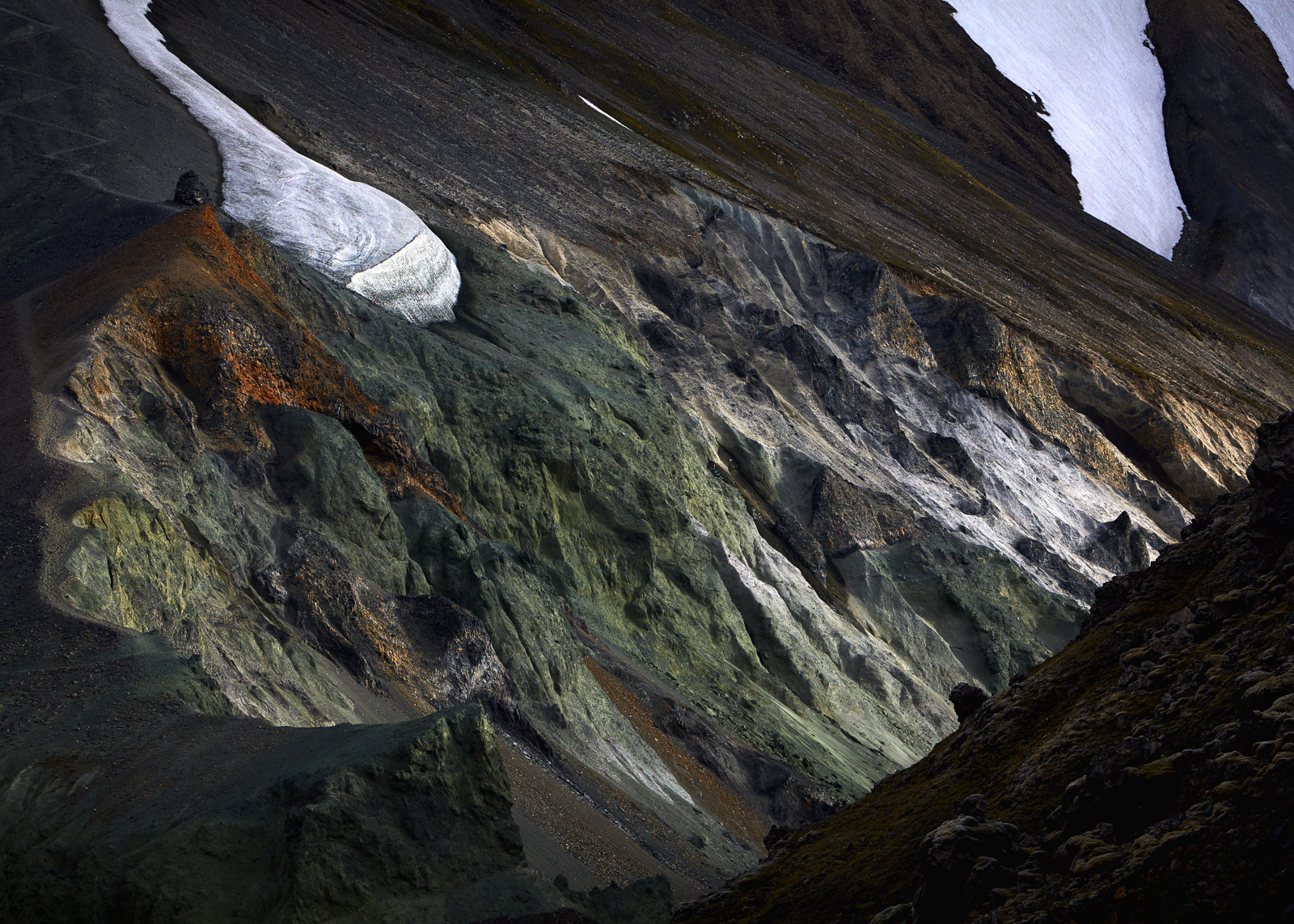

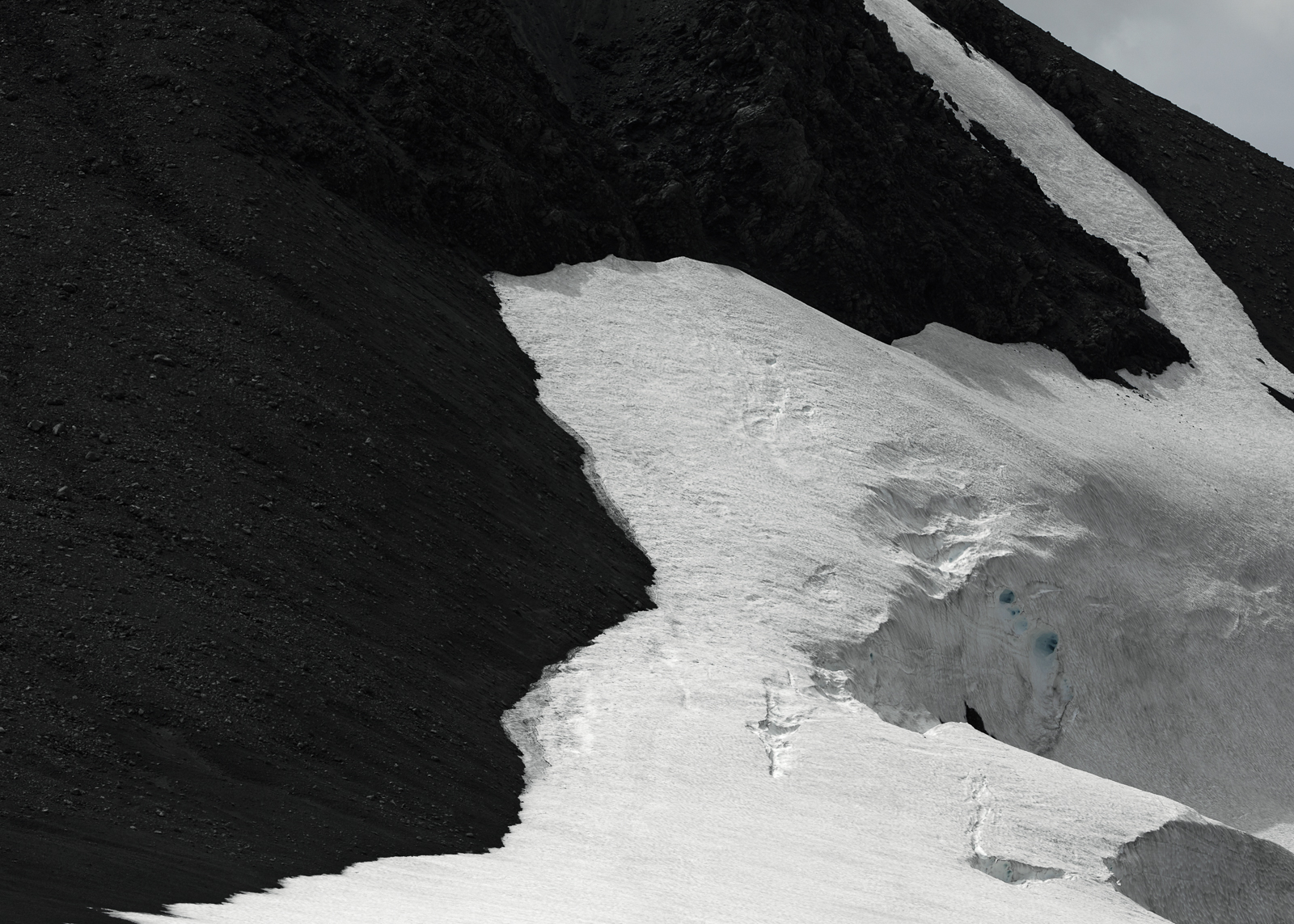

In Iceland - the Water and the Sky

Photographs by Tom Bunning In winter our thoughts turn to candlelit rooms and warming fires. But Tom Bunning's photography reminds us that the cold comes in many guises and draws our gaze to Icelandic landscapes - the waterfalls, the birds wheeling under eggshell blue skies and the endless snowbound vistas. Be warned though, if you venture out into the cold, you may not come back again...

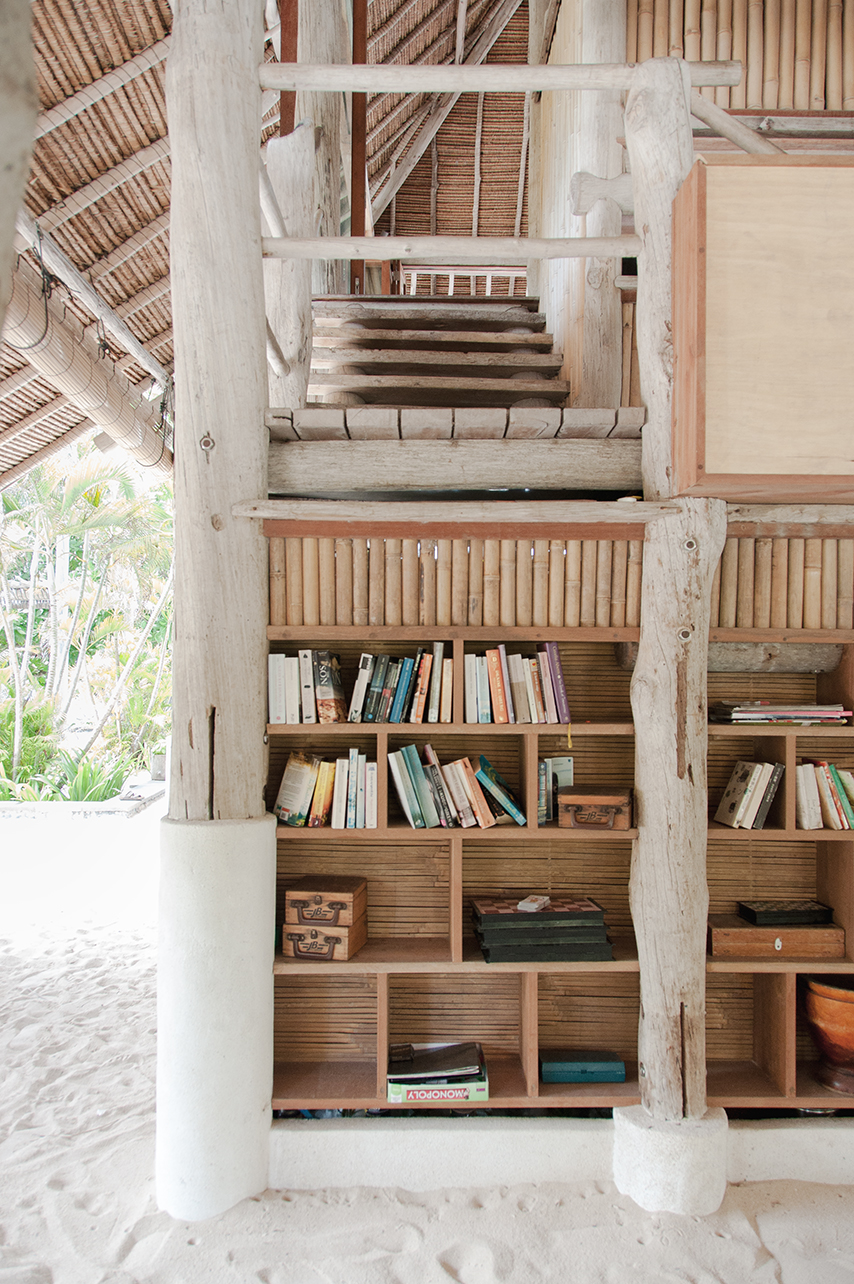

Nikoi Island

Flying from Australia back to London we had wanted to break up the trip by having a week to recharge and plan for the year ahead. Within easy reach of Singapore, and only eight kilometres from Bintan, Nikoi Island seemed to be the perfect option for us. A private island, 15 hectares in size, we stayed in one of the 15 beach houses that all sit facing the water.

Often most content just lounging downstairs in our beach house reading, we almost felt guilty for not taking up some of the activities that were on offer - such as snorkelling, sailing or a rainforest walk. For a week we enjoyed barefoot luxury and witnessed local fisherman on their boats under soft pink sunsets. We were a little sad to leave but grateful to feel relaxed and recharged for the year ahead.

Photographs by magazine contributor Renae Smith.

Etna Moments

Words by Ed Henry and Photographed by Renae Smith.

On an island off Italy’s boot you quickly learn that if it’s not Baroque, don’t fix it.

When you think of Sicily, what comes to mind?

The answers I received were split between those who hadn’t travelled there and those who had. The former would mumble something vague or hesitant - “it looks nice,” or “the birthplace of the Mafia right?”. The latter would gush a living eulogy for an island that captures the imagination and remains lodged there well after the holiday’s end. Now that I was visiting, I was suddenly a member of this club, the cognoscenti if you will. And in keeping with the island’s own warmth and generosity I will extend an invite, or provide a window at least, into this rocky triangular mass in the Mediterranean.

A whiff of context: Italy and I have history, from a grandfather who called it home to friends scattered across the North. I have had the privilege of seeing this country from many angles and so my objectivity is questionable. But this was my first jaunt to Sicily, and for my (much) better half, her first trip anywhere south of the Alps.

Sicily is a place that Italian mainlanders very consciously visit, such is the distinct identity that the island enjoys. Not forced, it is forged through the rich history that simply doesn’t exist anywhere else. Sicily is distinctly Italian, and the architecture and gastronomic traditions are on full display, alongside other axiomatically Italianate amusements. But it’s been combined and entwined with Greek flavours and Arabic influences, not to mention Spanish rule, and much more besides. I say this not to intimate a deep knowledge of the island but because it’s there for you to see, smell and taste. To the visitor more accustomed to the waterways of Venice or the sleek Milan cityscape, Sicily offers a warm, rugged and almost rough embrace.

Sicily, Italy

Trains do snake their way around the island, but your own set of wheels is thoroughly recommended. For a fully immersive experience, we plumped for a Fiat 500 (new model), but it wasn’t available, so they gave us one with a retractable roof. Oh fine, if you must. A less composed traveller would have squealed with excitement.

From Catania on the Ionian Sea we pointed the car north and meandered up the coast to our first base: Taormina, which is in no way defined by its undoubtedly touristy centre. We used the town as a launchpad for the surrounding area, and were handsomely rewarded. I do caveat that point, and indeed all of this article, by saying that we travelled in June. Intentionally so, as the temperature is a happy 30oC at this time of the year, rather than a sweltering 40oC plus. More crucially, we avoided the period between late July and the end of August which sees the mainland descend upon the island for tanning and indulgence.

Sicily, Italy

Once installed in our apartment (more immersive than a hotel), we spent days visiting nearby beaches, sunning ourselves on Spisone, sea kayaking around the grottoes and walking up Isola Bella. Later we trundled down the coast to Siracusa, a functioning commercial city. Whilst it does have spots for archeology enthusiasts, and some top eating experiences, the big draw is the historic centre, Ortigia. To be blunt, it’s stunning. An afternoon walking around Ortigia’s backstreets is sheer joy, the main square a deep white, dominated as it is by the Duomo - I didn’t think places like this existed anymore. Ortigia itself is an island off an island, so if you walk for much more than ten minutes in any direction you’ll come upon the azure abyss that surrounds it.

At this point you think you’re aesthetically there, at the apotheosis, and that you can relax with a cool beer. Not so, or Noto so - if you will. A winding 40 minutes’ drive away is Noto, which would scream UNESCO heritage site, if only it weren’t so tranquil. The cathedral gleams in the Mediterranean light, the numerous supporting cast of churches and palaces resplendent under the sun. It’s a visual feast, and if you’re into architecture, it will probably satisfy more needs besides.

The best way to wind down from such an experience is to step into one of the local ice cream shops. Not just any gelateria, mind. Where do you think the best gelato is? That place in Soho? Don’t joke. San Crispino in Rome? It’s up there. But the number one and number two are within 50 metres of each other in Noto. A locale called Caffè Sicilia sounds like a tourist trap, but it’s not. It does to your mouth what the rest of the town does to your eyes. I’ll leave it there, and say to you go. Go.

The inner island is matched in beauty by what you find on the coast - picturesque beaches lapped by clear blue waters. They all deserve a mention, but only one gets that honour. Riserva Naturale Orientata Oasi Faunistica di Vendicari, as the names suggests, is a nature reserve, one where you can walk through ancient ruins, jump (cautiously) from rocks into the cooling waves below, or tiring of that, find your own spot on the pristine stretch of coastline.

Sicily, Italy

Subsumed in the beauty of the landscape, we avoided Sicily’s cities apart from a brief drive through Catania. This city has more to offer than suicidal driving, but it’s a different trip. Its vibe is long weekend, not a week unwinding in the sun. The single greatest thing about the city however, is the elephant in the room of this piece so far. Mount Etna, which stands behind Catania, dominates the skyline up and down much of the coast, which means that you can have your own Etna moment no matter where you are as it’s visible from, well, everywhere. The classic way to take it in is from the amphitheatre in Taormina, although others prefer to see it in contrast with Catania’s urban grit. We found our Etna moment when looking down at the valleys and beaches from picture- perfect Castelmola, a hilltop town you wouldn’t believe existed until you saw it. The only thing towering over us? Etna herself. The millennial traveller is accustomed to mountains, au fait with tropical climate and quite frankly used to white sand. A volcano is a treasure of nature not often seen. If you leave Sicily in any doubt, you won’t arrive home with it; as the plane climbs into the sky it skims Etna just above her peak.

The food. Oh yes. I’ve saved the food for the end so as to contain it, for memories of my trip, as with much of life, are marked, or should that be stained, by what I ate at the time. The food here excites and subverts and is as much of an experience as any of the vistas. You farewell Sicily with a new found love of aubergines, you’ll remember how wonderful tomatoes can actually taste and best of all, you’ll discover that fish needn’t be dry, bland and deep-fried.

Sicilian food is independent of mainland Italian cuisine. The two styles are not unrelated, but think of Sicilian food as a proud cousin. The same historical and imperial forces responsible for Sicily’s formation, have brought similar import to its cuisine. This is not to say that classical Italian strands are not evident: my travelling companion’s dish of the tour was the definitive Pasta alla Norma served at La Piazzetta in Taormina. Named after the work of one of Catania’s most famous sons, this dish became almost a standard for restaurants up and down the east coast.

Not every meal can be indulged in print, but it would be remiss not to pull out a couple of highlights. Osteria da Carlo was a gem hidden in Ortigia. We had the legendary six- course fish menu, for the grand sum of €35, washed down with the best bottle of €5 house plonk I’ve ever swilled. If it swam in the sea nearby, then it was on that menu. You order sea bass, and not one, but two of the fullest, freshest fillets turn up, naturally served in the juice of the finest fruit Sicily has on land: lemon.

Flavours on the island, like the setting, shall not date. Consistency, textures, even viscosity are all different, all exciting. Entirely Sicilian. As Sicily’s perhaps most prominent literary son, Giovani di Lampedusa, proffered: “Sicily is Sicily - 1860, earlier, forever”. Long may she be, and proudly too. More’s the better for me, as I will be back soon.

Sicily, Italy

Sicily, Italy

Sicily, Italy

Tom Bunning

We met Tom Bunning in a coffee shop in South London where he greeted us with coffee and a portfolio. Understandably, we fell instantly in love with his photographed world, made up of etherial landscapes that play with light and scale and intimate portraits that capture the sitter's soul in the most artful way possible. We just had to chat to him about what makes his work so easy to get completely lost within.

We met Tom Bunning in a coffee shop in South London where he greeted us with coffee and a portfolio. Understandably, we fell instantly in love with his photographed world, made up of etherial landscapes that play with light and scale and intimate portraits that capture the sitter's soul in the most artful way possible. We just had to chat to him about what makes his work so easy to get completely lost within.

What do you love about photography?

Where to start. I think I love a photo’s ability to transport the viewer: be it back to a special memory; forward to a place they’d love to visit, or to give a glimpse into a person’s mind. But in less romantic terms, I’m basically a lazy painter. If I found that wielding a paintbrush gave me as much immediate pleasure as taking a photo does I’d probably be trying to do that now, probably rather badly. For me the greatest pleasure right now is to be able to earn a living doing something that I love. Fingers crossed that continues. I also really enjoy seeing other photographers’ work. I feel part of a community of like-minded souls, all of us trying to create something meaningful or beautiful or interesting, using photography to try to make sense of our world.

Can you remember the first photograph you took?

I don’t think I can remember the first photo I took, but I can definitely remember an early view that inspired me to take pictures. I grew up in a very small village in Suffolk, our home was surrounded by fields and the view from my bedroom window was of a giant oak tree set in the centre of a field. All year round I’d watch the colours of the landscape change and in the summer the old proud oak would stand tall in the centre of a bright yellow square of rapeseed flowers, the small window providing a perfectly framed photograph in my mind’s eye.

What inspires your work?

My inspirations have changed over the years I’ve been growing - both as a photographer and as a person. When I seriously started trying to take pictures for a living I was working at Abbey Road Music Studios (it sounds glamorous but I was mostly in a dark room QCing music videos!) so my early work was definitely inspired by rock and roll. I had several great years of shooting live gigs, taking portraits of musicians and touring with bands, interspersed with fashion work, which I think went hand-in-hand quite naturally. In recent years I think I’ve become earthier, more inspired by the natural world if you like, and I think this change in personal perspective has affected what I’m inspired to shoot professionally. One of my current projects is entitled Crafted and is a series of photos documenting and celebrating those in Britain who make the small, the hand-crafted and the individual. I’ve always been interested in England’s landscape and heritage and I suppose Crafted is an extension of this interest, focusing in closer on the personal aspect of our environment. On the flip-side, as my commercial work increasingly takes me further around the world, I’ve been enjoying capturing foreign landscapes.

How would you define your style?

I’m still developing as a photographer and my style will continue to change over the years but I like to think it’s honest, clean and simple. I don’t like to over-process or over-edit my shots and I always try to get what’s on the back of the camera as close to how I want it before it gets to the editing stage. Of course some clients know exactly what they’re after in terms of a feel or look of a shot and when that’s the case I think you have to find the balance between your personal style and their needs - always a challenge but a fantastic one. I recently had a great meeting with an agency and they described my work as having a ‘very gentle approach’ which was a lovely thing to hear.

Does travel influence your work in any way?

As I touched on above, it has done much more so recently. My commercial work over the last year or so has taken me around the world to all sorts of incredible places, from Seoul to Islay, from Vietnam to New York, Kuala Lumpur to LA, among others - although I should say that amidst all this excitement I’ve had many shoots in dirty parts of London to keep my feet on the ground! I think the thing about travelling for me is that as a full-time Londoner, living and working in the fast lane, being away gives me an opportunity to expand my view of the world and gives me time to see things I probably miss at home. Something that seems very ordinary to locals can look extraordinary through a foreigner’s eyes.

Has there been a particularly memorable project either past or present?

I would have to say my ‘Death Valley’ series from earlier this year, wonderfully displayed here by your good selves! One of my current gigs is working with David Beckham and his team for Haig Club Whisky which has been an absolute pleasure. In the grey depths of January I flew to the sunshine state for a promotional shoot for Haig. The shoot was only for the day but it would have been rude not to make the most of it so my assistant Danny and I stayed out there for a week, hired a car and took a road-trip from LA to Vegas via Death Valley where I spent several days shooting a series of landscapes. An absolute dream trip. The colours and expanse of the landscape out there were so rich and photogenic and I’m really pleased with the results.

What is your dream subject?

That’s a tricky one. In terms of humans I love photographing interesting faces, be they young, old or in-between. I’d love to turn my lens on someone like John Hurt or Morgan Freeman but equally so on a sheep-farmer or a dress-maker. Landscape-wise I have a real hankering to go to Iceland. I don’t have much experience of working with such a cold clear environment and, having recently invested in the new PhaseOne IQ250, I’d love to get out there with it and see what I can capture. My ultimate goal is to bring the two main aspects of my work closer together, working on location to take portraits of interesting subjects, set in interesting environments.

Where can we see more of your work?

I’ve recently had my new book made, by Cathy Robert at Delta Design who’s done a wonderful job, so I’m in the process of making appointments with agencies. Much of my recent work is showcased on my site at www.tombunning.com. I plan to exhibit the Crafted series next year in London so look out for that.

“You don't make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved.” ― Ansel Adams

Slow seaside travel in Toyama Prefecture, Japan.