Hotel Review: Langdale Chase

Slow foodie travel in the Lake District.

Covering more than 880 square miles - and comprising 14,650 archaeological sites, around 1,760 listed buildings and 23 conservation areas - the Lake District, England’s largest National Park, is defined by its waterways. Bestowed with UNESCO World Heritage status in 2017, the Park’s western edge is a place of extremes. It is home to Wastwater, England’s deepest lake, and Scafell Pike, the country’s highest peak (one of the first to climb and describe it was hillwalker Dorothy Wordsworth, William’s talented sister). You can swim in Blea Tarn, which took shape during the last Ice Age, or follow the Eskdale Trail to seaside Ravenglass, a Roman naval base-turned coastal hamlet. Windermere is further south and scattered with 19 islands. As one of Britain’s largest lakes, it is probably the most recognisable of the National Park’s 16 named bodies of water, but it’s easy to avoid the crowds by biking through the sculpture-dotted Grizedale Forest or walking up to Orrest Head. The view here is said to have inspired writer and illustrator Alfred Wainwright to pen A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells, a collection of seven books which have guided generations of enthusiasts since they were first published in the 1950s. As a fitting reward for his contribution to Lakeland tourism, the area’s 214 fells (uncultivated hills) are referred to as Wainwrights. Scotland’s Munros have a similar origin story, taking their name from Sir Hugh Munro, the first to list the country’s highest peaks.

Alternatively, you can escape it all by checking in to the heavenly Langdale Chase. With a hospitality history reaching back to 1891, this beautifully-restored, deliciously-welcoming hotel on the shores of Lake Windermere is not only a great place to abscond when you’re determined to do very little (in style), but is making waves on the culinary front.

When sitting in the two AA Rosette-awarded Dining Room over a scrumptious, sculptural dinner, it feels as if you’re suspended above the water; and if you don’t have time to stay overnight, at least visit for afternoon tea or lunch (make sure to order the sage-dusted beetroot gnocchi if it’s on the menu).

The adventurous can plan their day from the Boot Room (there’s a car on hand to deliver you to the start of walks), cocktails can be sipped in The Hall beside the original wooden staircase, and in the bedrooms the Lakeland views (Langdale Pikes and Coniston Fells are in your sights) are all the entertainment you need. Across the Grade II listed building, hues are inspired by the waterways and peaks, there are nods to the elegance of the 1920s and 1930s, and the terraced gardens feel like a refined oases - but if the weather proves too wild, you can always retreat to the cinema.

To capture the Langdale Chase magic, we wanted to share some of Daisy Wingate-Saul’s gorgeous, wintery images - because who doesn’t want to escape to the Lake District when the sky feels close, the landscape is dramatic, and the food on offer totally divine?

For more British travel ideas, check out our book - Slow Travel Britain - published with Hoxton Mini Press.

Return to Valle d’Aosta

Getting back to nature in Italy's north.

Words & Photographs by Chiara Dalla Rosa

Snow-capped mountains accompany us as we drive towards Courmayeur, our gateway to the Aosta Valley. These breathtaking views offer a captivating preview of the experiences awaiting us, with nature clearly set to be the star of our trip.

After leaving our luggage at Hotel Maison Saint Jean, our journey begins at Chalet Val Ferret, where we savour local charcuterie and traditional dishes, immersing ourselves in the region's essence. I opt for the gnocchi with gorgonzola cheese and pear, a delicious dish to fuel me for the hike ahead. The gentle trail my friends and I are following offers stunning alpine views and encounters with inquisitive marmots. With more than 300 walking routes to explore, the Aosta Valley provides endless opportunities to get amongst its dramatic landscapes.

Passing the 1,000-year-old Pré de Bard glacier, we catch sight of Rifugio Elena, our destination perched at 2,061 metres above sea level. This hut, a haven for hikers embarking on the renowned Tour du Mont Blanc (TMB), one of Europe’s most popular long-distance treks, is the ideal place to rest before starting our descent.

If you're craving high-altitude thrills (and want them as fast as possible), then look to the SkyWay Monte Bianco. This marvel of engineering whisks you from Courmayeur to Punta Helbronner (at 3,466 meters above sea level) in just 18 minutes. Its 360° rotating gondolas deliver out-of-this-world views of Europe’s highest peaks. It’s an unforgettable visual feast.

Although an unexpected blanket of clouds had descended upon arrival, I was fortunate enough to glimpse Dente del Gigante (Giant’s Tooth), a dramatic spiky summit within the Monte Bianco massif. After braving the brisk breeze, we find refuge in Bistrot Panoramique Punta Helbronner, where we enjoy a meal while basking in yet more soaring views.

Returning to a lower altitude, we’re eager to lace up our walking boots once more. In La Thuile, we meet Ettore, our guide for the afternoon, and embark on a leisurely hike to explore the Rutor Waterfalls, natural wonders that feed the Dora River. Unable to resist, I find myself repeatedly stopping to take in the details: the warm, variegated hues of the cedar trees, the rugged grey slate, and the rich auburn tones of the boulders around us. Upon reaching our destination, a vibrant rainbow arcs through the mist of the cascading falls. With our goal for the day accomplished, we trot down quickly, eager to return to Chalet Eden, where a relaxing sauna and aperitivo by the river await us.

The following morning brings a new adventure, this time on two wheels. Although I’ve tried e-biking before, this experience is more raw and intense. We board one of the chairlifts in La Thuile which takes us up to the start of a freeride track. From there, we ascend to 2,400 metres, pushing ourselves to new heights. At the top, the alpine panorama leaves me spellbound. A sublime blend of awe and fear washes over me as I feel the immense power of nature feeding my soul - a sensation that is equal parts peaceful and overwhelming. And the excitement continues as we begin our downhill ride. If you’re craving the rush of speed, this heart-pounding experience is exactly what you’ve been waiting for.

After our exhilarating ride, we’re elated to sit down for lunch at Lo Riondet, a charming family-run restaurant. The menu features locally sourced dishes and wild game hunted by the owners. During our meal, we chat with Dan, our mountain bike guide, who is clearly besotted with the area. “I love the trails here,” he says with a smile. “This region offers natural bike parks with Alpine terrain, something I’m addicted to.” As he accompanies us back, we ask about his plans for the rest of the day. His eyes light up as he reveals that he’s heading back up the mountain for another downhill session, a true testament to his passion for the sport.

On our final day in the Aosta Valley, we explore its capital, a city rich in Roman history and shaped by eclectic cultural influences, situated at the crossroads of France and Switzerland. With Hotel Duca d’Aosta as our base, we spend the day sightseeing and museum-hopping. We delve into the Roman heritage, discovering how the ancient city was constructed. We visit Issogne Castle, where we read stories etched on the walls by past guests. We also explore the charming Bard Fortress, home to the Museum of the Alps and a filming location for one of the Marvel movies. To round off our visit, we indulge in some delicious cheese and salumi at Erbavoglio before bidding a fond farewell, at least for now, to this breathtaking region.

This is an experience I will treasure and revisit in my memories time and again. It’s remarkable how much we accomplished in just a few days. Nature was undeniably the highlight of this journey; I felt its presence all around us and understood why locals hold such deep affection for their beloved region. Once you’ve explored this beautiful land, you’ll undoubtedly find yourself drawn back.

To learn more about Aosta Valley and discover all the activities you can embark on, check out their website aosta-valley.co.uk

Island Escape

Citizen Science - a stay with purpose at Banyan Tree Vabbinfaru.

Words & Photographs by Daisy Wingate-Saul

I slip into the warm embrace of the shallows, clumsily struggling with my mask and flippers like a fish out of water. Phoneless for the first time in what feels like months, I follow my snorkelling guide through a cleft in the reef, taking care to avoid disturbing the fragile coral, whilst not inhaling the salty water gurgling in the bottom of my snorkel.

Just as I calm my breath and settle into my new surroundings, the reef abruptly falls away and I float over the edge of the abyss, my body suspended, weightless. Tropical fish dart in and out of coral caves while sleek black-tipped sharks glide silently past me, dappled sunlight dancing on their cigar-shaped forms. This underwater paradise is a world apart from the turbid British coastline I am used to.

Arriving at the island resort of Banyan Tree Vabbinfaru by speedboat feels like stepping into a scene from a Bond film. The beach villas - each with their own pool, nestled amongst swaying palms and encircled by coraline sand - offer a back-to-nature sanctuary within the North Malé Atoll. From Asian-inspired spa treatments to the Japanese-themed sustainable restaurant Madi Hiyaa, it’s easy to settle into the luxurious rhythm of island life. But it is on the reef, cascading into the depths of the Indian Ocean, that I truly relax.

“So, what do you think coral is?" asks Henry, our resident marine biologist, as my partner and I take a break on land from sea exploration. "Um, a crustacean?" I offer tentatively. Henry chuckles politely before enlightening us. "Actually, corals are formed by tiny slow-growing organisms called polyps that eat plankton and build protective calcium carbonate skeletons over time, creating these vast, colourful structures that support the diverse underwater ecosystem”. Coral reefs play a vital role in safeguarding the planet by protecting and supporting coastal areas, livelihoods, and diverse marine species - which is why coral is often called the forests of our oceans.”

These words resonate with me, reminding me of the practice of 'forest bathing,' (or shinrin-yoku in Japanese), which promotes immersion in nature to boost physical and mental wellbeing. I’ve experienced the mindfulness and relaxation that comes with forest bathing many times before (I seek out green spaces when my mind gets busy), yet finding a similar calm in a complex underwater world was completely new to me.

Sadly though, rising sea temperatures and other environmental factors pose significant threats to coral reefs. This is vividly evident in phenomena such as ‘coral bleaching,’ where stressed corals expel their vibrant algae, turning healthy reefs into white graveyards. Consequently, once-thriving ecosystems, even in remote places like the Maldives, are now experiencing rapid decline.

Since the establishment of its groundbreaking marine lab in 2004 though, Banyan Tree's marine team has led the charge in safeguarding and restoring the delicate marine ecosystem surrounding its properties. Through collaboration with visiting scientists, involvement of the wider community and education of tourists, the resort's conservation efforts extend well beyond its sandy perimeters.

The citizen science program at Banyan Tree offers guests the unique opportunity to participate in guided snorkelling and diving sessions, where they can witness the beauty of coral reef nurseries, actively engage in coral planting and restoration efforts, and contribute to valuable data collection initiatives. On terra firma, guests can attend informative marine talks, gaining a deeper understanding of the crucial role these reefs play in safeguarding our planet's biodiversity.

I join a reef cleanup on Banyan Tree's sister island, Dhawa Ihuru. Setting off on a snorkelling expedition along the island's remarkable reef, we meticulously survey it for coral-eating 'crown-of-thorns' starfish, each of which has the ability to devastate up to ten square metres of coral bed annually by releasing digestive enzymes, effectively transforming vibrant reefs into coral soup. With their natural predators like the giant triton now extinct in the Maldives due to shell hunting, the responsibility to reduce them falls upon us. Armed with a floating bucket and a hooked stick, our task entails severing them from the coral and ceremoniously burying them in the sand.

With each slow breath taken beneath the surface and the sun's warmth on my back, tension melts from my salty body. In a final underwater dance, buoyed by newfound confidence in my mermaid-like abilities, I dive down towards a cave in the reef's edge. Inside lies a nurse shark resting in the shadows and in its quiet presence, I can think of nothing but the creature before me. It’s the ultimate escape from the noice and bombardment of everyday life. I emerge rejuvenated and fresh, the sensation akin to the clarity found after a soul-stirring stroll through an ancient woodland.

A stay at Banyan Tree extends beyond a luxurious moment in paradise; it presents an invaluable opportunity to delve into the mysteries of our underwater forests. Who can say what wonders lie beyond the rocky shores, waiting to be discovered upon my return home?

To learn more about the resort, or book a stay, click here.

A Play Unfolding

Exploring Andalucía on horseback with George Scott.

Words by Emma Latham Phillips & Photographs by Daisy Wingate-Saul

Exploring Andalucía on horseback with George Scott.

First published in our Spain magazine

From the balcony, I look out across a landscape lit by stars. A waxing moon illuminates the curves of olive tree-lined hills, while scattered farmhouses emit faint glows. There’s so much silence outside, nothing but the night, the smell of the earth and the sharp November air. Yet behind me, in a room awash with candlelight, people have begun to dance. Their voices rise and fall to the soft strikes of a piano and the strumming of a guitar as they swap stories like old friends. I stare back in a dream; it’s as if I’m watching a sequence from an old movie detailing a life that couldn’t possibly be mine. The scene is too Technicolour, too full of laughter, too utterly devoid of worries.

We met just a day ago, seven strangers and a team of carefree ‘cowboys’, and today we’re letting go of secrets as fast as our cocktails are being poured. “It’s just like the beginning of a murder mystery,” Kerry had mused as we introduced ourselves that first evening. Over the next few days, we’re to witness what happens when you put a group of unfamiliar faces together in a beautiful place, give them incredible wine, food and conversation, and set them upon horses. The result is transformative - we re-learn how to live.

We’re joining George Scott for a three-day ride through Andalucía’s Sierra Norte de Sevilla, embracing the aching limbs and clear minds that come with spending 14 hours a day in the saddle. The trip starts and finishes at George’s family home, Trasierra, stopping halfway at Taramona, a part-ruined, part- everything-you-could-ever-need traditional Andalucían cortijo. During the day, we ride the cattle trails of George’s childhood, exploring a landscape that, while located only two hours from Seville, transports me into the pages of a Hemingway novel. George has spent the past few years poring over maps and pulling these forgotten routes out from beneath the brambles, persuading landowners to return them to their former purpose.

Like the farmers, merchants and bandoleros that have gone before us, our merry band of outliers traverse the trails that tie together the Sierra Norte National Park. We wind between olive and almond groves, our horses’ hooves leaving clouds of pink dust in their wake. Below us, rounded hills lie like a fistful of fallen marbles. We push gnarled branches away from our faces as we descend into emerald valleys scissored into segments by the Huéznar River. Here, we find whitewashed farmhouses ensconced like opals amongst quaking aspen leaves. Pocket-sized vineyards slip into the grips of late autumn, a mass of red and orange made more vibrant by the bright blue sky.

Even in November the trees are still heavy with fruit, and in front of me, George picks walnuts and figs as he rides. “Wine?” he asks, throwing me a traditional bota de vino (wineskin). This is a phrase he repeats warmly over the next three days. I accept and squeeze the liquid into my mouth while trying not to lose control of the horse. George canters ahead, a cigarette in his mouth, riding up to chat with his friend Jaime Guerra. Jaime is head of horses and has grown up alongside George. He rides a palomino the colour of a winter sunrise, with a bottle of sherry in his saddlebag and Mafalda, the Spanish terrier, at his heels. I watch the two of them talk and laugh, as comfortable on their horses as if they’d been born on them.

I am quick to fall in love with the rhythm of the days. Get up, ride, eat lunch, drink wine, ride, eat dinner, drink wine, dance. The ride becomes an hours-long meditation, my mind falling in time with the gentle clip-clopping of hooves and chime of nearby sheep bells. I don’t think or see anything beyond the moment and the thyme-scented hills ahead. Our horses do not falter as they move through difficult terrain, and they break into exhilarating canters upon reaching holm oak meadows and dusty roads. You need to be completely at ease on a horse to travel like this.

“I really believe the pace of these rides is natural to the pace of life we are designed for as human beings,” George explains. “Guests leave technology aside for a moment and let go.” Brought up in these surroundings, and by a passionate mother, George knows that wealth doesn’t mean money - and his trips reveal the true definition of luxury. Here, you’re left with the absolute best of everything you need: good company, the trust of your horse, fine local ingredients, the scents of the land and the openness of the sky. This is a chance to escape the madness of the modern world.

George’s mother, Charlotte, dreamt of a life that was a little different, and that’s exactly what she created. She and her husband left London in 1978 to return to the country of her youth, buying Trasierra and saving it from disrepair. They lived in the only room still standing and built the home around them, suite by suite. Charlotte pieced together the interiors like a collage, combining antiques, repurposed relics and furnishings of her own design to create an intoxicating mix of English cosiness and Spanish sensuality.

The first six years at Trasierra were spent without electricity, and Charlotte’s four children were brought up on books, flamenco and the chatter of guests. To keep her dream alive when her husband left for London, Charlotte turned Trasierra into a “hotel for those that don’t like hotels”, and today the house can only be rented as a whole.

George shares his mother’s desire to live life like a poem, revelling in the beauty found in simplicity, and making the little moments spectacular. Lunches appear in the landscape as if a curtain has been pulled back. We find our table silhouetted in the sun beside a shimmering reservoir, beneath the bowing leaves of willows. On the patterned tablecloth, Ezequiel Bressia, a Mallmann protégé, lays out the traditional Andalucían fare. There’s lentil stew, white-garlic gazpacho, potato tortilla, cheeses and acorn-fed black Iberian pork. We sip wine and then sherry as Ezequiel moves off into the meadow to find more field mushrooms to grill. And we finish our lunch with alfajores, shortbread sandwiched between sweet dulce de leche.

But it’s at Taramona that the theatre reaches its climax. “I’ve created different stages in the different parts of the building,” muses George. His part-time home sits high above the surrounding olive groves. There’s a ruin on one side that’s deliberately been left unsalvaged, and an open room with an altar. As night falls, candles and torches are lit and their flames illuminate the crumbling stone, leading us to the dining table upstairs. There’s an air of romance to the whole affair, and after dinner, as George sits down at the piano, I realise that he is the circus master and this is his great show. His wit, charm and enthusiasm flood the experience with an endless energy.

It’s hard to return to normal life after witnessing a world like this. Though the days feel extraordinary, they’re somehow more real than anything I’ve ever experienced. For too long I’ve kidded myself that technological progress and convenience is freedom. But here I was learning what true adventure feels like, and embracing the addictive joy that comes with riding free-spirited horses through tree-spattered meadows.

A Sunburnt Country

An Australian road trip with photographer Grace Elizabeth.

Lodestars Anthology contributor Grace Smith has just launched her new print shop that features some of the images she captured on her road trip from Brisbane to Uluru - an Outback adventure we included in our recent Australia magazine. To celebrate, we’ve shared a few glimpses of her work below, paired with the lyrical musings of writer Sarah Jappy. To view Grace’s full collection click here. For now, here’s to open roads and endless skies.

Poring over Grace Smith’s ochre, umber and gold images of the Australian outback on a late-summer afternoon in my South London study, I feel like someone receiving postcards from outer space. Not least because of the vast, lunar landscapes, pockmarked craters and incandescent glow of Uluru and Kata Tjuta at sunset - settings Grace describes as ‘Australia’s version of Monument Valley’.

It’s also the disparity between viewing these images from far away, feeling dwarfed by the epic beauty of landscapes never encountered but often imagined; scenes so powerful they moved Grace to tears. “I was speechless, it is so beautiful in person. It takes your breath away. Driving makes you appreciate it more because you’ve done the kilometres to get there. I didn’t expect it to be so emotional.”

Add to this my two-year sense of longing, a pining for distant lands and extraordinary scenery, for warmer climes, for unfamiliar faces: a wanderlust that burns, despite the dampening, life-shrinking effects of Britain’s multiple lockdowns in 2020. Even with restrictions lifted and vaccinations taken, travelling to Grace’s remote scenes feels like a giddy dream, a sun-drunk impossibility - incomprehensible to think it was once so easy, so unquestioned.

Studying photos of Grace’s road trip from Brisbane to Uluru brings Australia back. That dazzling light, those startling colours, a sky so vast, a horizon so limitless, the minutiae of nature and human life. Grace says: “Our sun is so beautiful, but it’s strong. And the colours - there’s a vibrant rustic-ness to it. It’s an outback palette, it’s incredible to shoot. In the city, there’s all this maximalism, but then you go out there and it might be the smallest thing, like bougainvillea on a petrol pump, it’s the one thing that stands out that’s so beautiful.”

Looking at her photos, I can almost feel the vibrating heat as the sun warms discarded sheets of corrugated iron. I remember languid Australian afternoons that called for impromptu siestas, sunhat close by. According to Grace, Lester Cain - photographed snoozing on the veranda of his Middleton pub - would swap between napping and conversation, nodding off between comments.

As I look, the photos become a kind of visual sustenance, an ephemeral warmth. Washing drying in the sun. A haze of raspberry-pink flowers. The promise of a good night’s kip from a blinking, ruby-red ‘ROOMS’ sign in Winton. A flock of egg-yolk-yellow birds in the trees like autumnal leaves. Denim-blue and ombre skies, where swathes of gunmetal-grey blend into peach-pastel stripes. A golden road that yawns ahead like an unanswered question

For Grace, the road trip was a means of experiencing life differently: “There’s no pressure. You can see things for what they are. It’s really wholesome. It all comes back to that slow, holistic living and how you experience things in life, and I got to do that through my lens.”

Having the freedom to slow down and capture what counts, whether confined at home, in the middle of an epic road trip, or immersed in the vastness and subtleties of our daily lives, is our challenge. Recalling these learnings is essential - and photographs like these are our tools.

Grace and Sarah’s full story was published in our Australia magazine.

Spies in Middle Earth

Beyond the raclette, rösti and wildflowers - there’s more to Mürren than meets the eye.

An extract from the Switzerland magazine - Words by Cameron Lange & Photographs by Holly Farrier

In 1911, a teenage J.R.R. Tolkien set off “on foot with a heavy pack” into the Bernese Alps. Accompanied by a party of 12 family friends - let’s call it a fellowship - he spent several weeks crisscrossing the highlands in what turned out to be one of the most fateful treks in the history of English letters.

While the region was already of literary interest, notable as the place where Sherlock Holmes ‘dies’ at the hands of Moriarty, the landscape proved an even greater influence on the young Tolkien. Never in his life would he see mountains of that size again, and for the next 50 years his memories of them shaped the richly imagined world of Hobbits and Orcs in The Lord of the Rings.

It was the first part of his adventure, from Interlaken to Mürren through the Lauterbrunnen Valley, that left the greatest impression on him. There is much to suggest that the valley was the model for Rivendell, the Elvish city where the Hobbits find safety on their journey. Tolkien’s own illustrations of the refuge, marked by sheer cliffs and cascading waterfalls, are reminiscent of certain Lauterbrunnen postcards, and a dedicated sleuth will note the familiar name of Rivendell’s main river - Loudwater, and its Elvish translation, Bruinen.

Mürren’s surrounding peaks were also the direct inspiration for the Misty Mountains. While camping near Mürren, Tolkien found himself, like today’s visitors, in awe of the three great peaks visible across the valley - Jungfrau, Eiger and Mönch - which in his saga became the triad of Dwarvish mountains towering over the mines of Moria. Tolkien confirmed as such much later in a letter to his son, in which he recounts looking out over the vista and seeing “the Silvertine of my dreams” - the legendary mountain where Gandalf is reborn as the White Wizard. Gazing up at those same heights at sundown from the balconies of Mürren’s Hotel Edelweiss, it’s difficult to tell where our world ends and Middle Earth begins.

Tolkien’s debt to the Bernese Alps is still not widely known. The highlands and broader canton are more commonly associated with the world of espionage - both real and imagined - and with one particularly iconic James Bond scene. At the summit of Schilthorn stands Piz Gloria, the building made famous by On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, George Lazenby’s one and only appearance as 007. Now a revolving restaurant with cloud-draped views worth travelling for, it served as the secret hideout and nefarious research centre for Bond’s archnemesis, Ernst Blofeld. There Bond is briefly held captive, only to stage a daring downhill escape to Mürren on skis - a fitting chase considering the mountain played host, in 1922, to the world’s first slalom race. Had the film been made today we might have seen Bond attempt the fiendish via ferrata from Mürren to Gimmelwald, a hiking and climbing route clinging just barely to the cliffside - one of many gravity- defying activities on offer for the visiting daredevil.

Indeed, Bond has had some of his best moments in Switzerland, the most dramatic and celebrated of which is perhaps Pierce Brosnan’s leap from the Verzasca Dam in the opening scene of GoldenEye. After all, 007 was born in Zürich to a Swiss mother and the country has, by virtue of its neutrality and hellacious geography, always been rife with international spycraft - as well as writers looking for stories in or at the edge of that underworld. Both Ian Fleming and John le Carré studied in Switzerland, while W. Somerset Maugham arrived as an operative at the outset of the First World War. His brazen cover? That he was writing a series of stories about spies.

Behind the tranquillity of these photographs lies an arena of fantasy and political intrigue. The anonymity of the mountains gives some the cover to hide and scheme, others time to rest and dream - and for the young Tolkien, the chance to imagine a whole new Earth.

Interview - Tina Sturzenegger

Chatting with Swiss photographer Tina Sturzenegger.

While travelling in the land of René Burri, Photo Basel and vistas that defy description, it felt right to discuss art and alpacas with a contemporary Swiss photographer whose work is anything but ordinary. Tina Sturzenegger is a cheese-lover famed for her images of flower-bedecked farm animals and fusions of Pop Art, cityscapes and food - and from the moment I came across her vibrant creations in the pages of Transhelvetica (a publication dedicated to Switzerland) I was obsessed, aware that she’s someone who sees the world a little differently. Self-taught and infectiously passionate, Tina’s projects will make you smile, salivate and pack a suitcase.

An extract from the Switzerland magazine

What do you adore most about photographing food and animals, your subjects of choice?

It’s about composition and feeling. Sometimes I get to work with human beings, which is fun, but when I can shoot food, local farmers or animals there is a fire in me that starts to burn. I don’t have that ardently with humans ... it’s hard to explain in words. It’s just the thing I love to do the most because of the colours, the structure of the food, how it changes when you start to cook it and becomes something different. Farm to table, raw product to dish, that’s what fascinates me.

It’s a joy to work with and interview chefs, many of whom are both brilliant and bonkers. What’s it like to collaborate with the chefs of Switzerland?

My relationship with chefs in Switzerland is pretty good because I’m mad too ... When I work with someone I talk a lot and ask questions and they see my passion, what I’m burning for, what I’m doing, and they’re like ‘hey, we have the same passion’, and you start to connect very quickly. Some of the time we’re going nuts together and have a pretty good time ... Young chefs these days are cutting edge. Go a bit over the top, be honest, then you start to connect and create something great.

Has there been a foodie project that’s been particularly memorable?

I love all my projects but the fun part for me is when I have carte blanche and can do whatever I want. Like with my UMAMI story, or when I shoot drinks. For the UMAMI story they [only] told me that they needed five products pictured so I was doing stuff like freezing fish. My favourite project is my Mangascape story; it’s a mix of food and landscape shot all over East Asia. The things that I love most, China and food, go together pretty well.

Can you tell me a bit about your flower-crowned animals?

It was in 2015 and I was driving around Switzerland and Germany for a job and on the radio they were always playing Lana Del Rey, with the flower crowns, and I started to picture it and was like ‘no, let’s do Lama Del Rey. No, Alpaca Del Rey!’ I’m a huge animal lover so I Googled farms in Switzerland that had alpacas ... I met one who was super lovely and open and was happy to work with me and show me all of their [animals].

What do you enjoy most about working on the road?

Shooting when travelling is excellent. You always get surprises, instantly. You’re walking around and bam, there comes a building and bam, there comes a wall. It’s like a treasure hunt, you’re hunting for your pictures. It just makes me so happy. It’s not about the travel itself, it’s more about finding stuff.

You say there’s a craziness to you style - is this something that has changed over the years?

You develop yourself all the time. You always have your influences, you always get trends popping up and you notice them and combine them with your own [practice]. That’s the cool thing with photography, that you’re developing yourself the whole time, you’re challenging yourself ... You can be happy with what you’ve achieved to this point but you need to have a fire to do more and go bigger and be better.

Storms & Silence

Getting wild in the Norwegian Arctic.

Words & Recipes by Kieran Creevy - Photographs by Lisa Paarvio

This was a dream project, three years in the making. But with less than a week to go, the weather gods are in a capricious mood.

Norwegian Arctic, the beginning of March and I’m staring out at jagged mountains. Instead of white peaks, grass, mud and stone are clearly visible. There used to be solid sense of predictability to the seasons. Now, winters are fickle, areas that should be covered by metres of powder are scraping by with centimetres, or in our case, bare grass and stone.

Then, it happened. With less than a week to go, the skies darkened precipitously, that beautiful blue-black that heralds snow. More than a metre falls overnight - and it keeps coming.

The team meet at Tromso airport, the car is packed with winter gear, while surfboards and snowboards are strapped tight to the roof, and we head into the night. Wipers own high, driving into thick snowfall. Our speed drops to 40kph, but we’re feeling invigorated.

Alarms sound early. Though the skies are dark with more snow on the way, there’s a stark beauty to this area, as though the land is painted in monochrome. Mugs of tea in hand and maps spread out, we fire up the forecasts and avalanche assessment pages.

To no ones surprise, the weather has changed. From one extreme to the other. Once green and brown mountains now lie deep under snow. However, this swift shift brings its own risks. From an avalanche risk of one, it’s shot up to four on many slopes. Steering clear of loaded slopes, we plan routes that minimise risks and give us time to dig pits, getting first-hand knowledge of what’s happening under our skis and boards.

Clipped into skis and splitboards, we head out, not knowing what we’re going to find, but eager for the search. The zip and hiss of climbing skins on hard, packed snow, smooth strides, accepting we have hours ahead before we reach our chosen basecamp. Wild, open, mountains to our back and black water below.

Tents pitched, guyed against potential storms, we’re planning our first foray into the hills when, as if linked by telepathy, my companion’s (Lisa, Ben and Kate’s) eyes turn to the inky black sea, where maybe 200 metres offshore waves are breaking in beautiful curled shapes. Soon the trio are slipping into the liquid darkness, transformed into seals, insulated against the chill.

Hours later they emerge, ice forming on strands of hair, the wetsuits beginning to stiffen in the deep cold. In dry clothes, swaddled in toasty warm winter sleeping bags, we listen to the comforting roar of the stove, good food warming us physically and psychologically.

Arms aching slightly from the hours in cold water, its time for our legs to burn.

Sparkles of light reflecting off the snow from the beam of our head torches. The land cloaked in darkness, the heavens above glittering with a million points of light. Snow crunching under our skins as we make our way steadily uphill through deep snow and forested hillsides. As we get closer too the peak the first rays of days cast their warmth on the land.

In front of us opens a stunning view over the Arctic Ocean, deep fjords and icy peaks, a feast for our eyes. A sense of tranquility sets in. Silent within the team. A moment suspended, taking it all in. In front of us lies a day of whoops and hollers, wide grind under ski goggles. Hours of carving lines in fresh powder, rinse and repeat again and again.

There’s something so wonderfully simple about expeditions, especially in winter. What matters gets stripped down to essentials.

Earth - what the land gives us, both in terms of food to fuel our adventures, and as a magical playground.

Fire - the fire to warm our food, the fire in our souls, fuelling our dreams.

Air - each inhalation of breath helping to power our muscles, the deep gasps as the slopes steepen on the skin tracks uphill.

Water - to keep us hydrated, and the circularity off what falls from the sky in this wonderful powder snow will eventually melt and help fuel the next cycle of rain, ice and snow.

I’ve had a few people tell me that they think sounds, smells, colours are muted in winter, but I’d respectfully disagree. Sure, with grass and wildflowers hidden under a blanket of snow, there isn’t the medley of colours, but just look at a snowfield, under blue sky or cloud. There’s this wondrous subtlety to the shades of white, depending on where light falls. To open a tent door to a bluebird day, there might only be one primary colour - but how that looks bounding off pristine snow. For me, these moments are priceless.

Days pass all too fast; whoops of elation as we carve lines downhill; crystals of ice on a water bottle turning a sunbeam into a rainbow on the snow; ski jackets steaming at the top of a climb; and mugs of soup warming us as we sit on our packs, eyeing the contours for our descent. Camera gear gets saturated; climbing skins, damp with moisture hang on lines in the tent, drying overnight. But all of these are minor problems compared to the elation of being able to play in this magnificent wilderness. Two weeks ago, we worried this trip might not happen. Now…

Arctic char, barley, pepper and onion. Serves 4

Ingredients:

250g barley (can be substituted with couscous, bulgur or rice)

1 litre water

1 vegetable stock cube

1 tsp salt

2 tsp ground black pepper

1 large red pepper, diced finely

1 onion, diced finely

500g hot smoked arctic char (can be replaced with hot smoked river trout or salmon)

Method:

Heat the water to boiling

Add the salt, pepper, stock cube and barley, cook on a simmer until tender

While this is cooking, dice the pepper and onion

When the barley is cooked through, flake the hot smoked char into the pot along with the pepper and onion.

Mix well and serve

Oatmeal, skyr, raspberry. Serves 4

Ingredients:

280g oat flakes

800ml water

50g butter

200g skyr

200g raspberries or other fruit

2 tbsp apple syrup or honey

Method:

In your stove, bring the water to the boil.

When boiled, turn off the heat, add the oats, butter and syrup, mix well.

Cover and allow to soak for 3-4 minutes.

Serve with spoonfuls of skyr and fruit.

Recipes from Glebe House

The East Devon bolthole you’ve been dreaming of!

Overlooking the Coly Valley in sunny East Devon, Glebe House is a six-bedroomed retreat (with a cabin) that, despite being only a short, serpentine drive from the Jurassic Coast, feels far from the madding crowd (excuse the line, but this is Thomas Hardy country after all). This guesthouse is a true pastoral escape, a place where the landscape is celebrated, slowing down becomes an art, and evenings begin with sunset cocktails as you watch cows saunter though the neighbouring paddock.

Known as a restaurant with rooms - or rooms with a chef - dinner is the star attraction, whipped up by chef and Glebe House co-owner Hugo Guest, who grew up here and is passionate about local produce and the slow food ethos. Everything tastes as if it’s just been plucked from the earth, pulled moments ago from the tiled oven or cured in his purpose-built ageing room.

Much of the decor is the work of Olive Guest, a third generation artist who paints brilliantly-hued abstract landscapes. The eclectic array of vibrant art is balanced by the home’s Georgian bones, and the chic bohemian vibe. There’s a glass entrance draped in vines and canvases, hand-painted lampshade inspired by the Bloomsbury set, and newly-upholstered vintage furniture in every pattern imaginable. Few places feel quite so brilliantly creative, or come with such bucolic views.

This description was written for Slow Travel Britain - a book to devour is you’re keen to explore England, Scotland and Wales.

To capture the Glebe House magic (until you can visit of course), the team have shared one of their fab seasonal recipes.

A Warm Autumnal Salad of Winter Mustard Leaves, Roasted Squash, Braised Shallots & Walnut Dressing

Ingredients:

- A mix of peppery winter mustard leaves (such as at wild rocket, mizuna, red and green mustard frills)

- 1/4 crown prince squash, seeded, and cut into chunks

- tsp dried chilli flakes

- tsp dried oregano

- 4 shallots

- 1 cup walnuts, heavily toasted and roughly chopped

- 1/4 cup light olive oil

- Zest of 1 lemon

- 1/4 cup grated Parmesan cheese

- Juice of 1/2 lemon

- Grated pecorino cheese, to finish

- Salt and pepper to taste

Instructions:

1. Preheat your or oven to a high heat (200deg)

2. In a large bowl, toss the squash squash with a good glug of olive oil, dried chilli flakes, oregano, salt, and pepper. Roast the squash until it is tender and slightly caramelized, about 20-25 minutes. Remove from heat and set aside.

3. At the same time as the squash, place the whole unpeeled shallots on a baking sheet, drizzle with olive oil and roast until they are soft and gooey. Circa 30mins. Set aside to cool slightly.

4.While the shallots and squash are roasting, prepare the walnut dressing. In a blender or food processor, pulse the toasted walnuts until they resemble bread crumbs. (NB you still want a bit of texture and crunch from the walnuts)

5. Transfer the blitzed walnuts to a bowl and add the light olive oil, lemon zest, grated Parmesan cheese, lemon juice, salt, and pepper. Mix well until all the ingredients are combined and resemble a loose dressing/pesto. Season with salt and pepper.

6. Once the shallots have cooled slightly, peel off their skin and slice them into thick rounds, season with salt and pepper.

7. In a large serving bowl, arrange the mustard leaves. Top with chunks of warm roasted squash and the roasted shallots.

8. Drizzle the walnut dressing over the salad, tossing gently to coat all the ingredients.

9. Finish the salad with a generous sprinkle of grated pecorino cheese.

10. Serve the warm autumnal salad immediately.

Florentine Allure

Discovering Italy with Villa San Michele.

An extract from the Italy magazine - words by Liz Schaffer & Photographs by Mattia Aquila

Florence is a city with a past, a Tuscan icon synonymous with Medici intrigue, the Renaissance and art. What comes as a surprise though, is the fact that the latter is indebted to the guilds - corporations of workers such as merchants, bankers and silk weavers, established back in the 13th century, who funded much of the city’s artistic output (while also gathering taxes and keeping secrets). The wool guild sponsored the Duomo and David, while the Baptistry’s bronze doors were financed by cashed-up textile merchants.

Artists themselves were also part of the fold, in a guild with physicians and apothecaries. Although both professions used the same essential ingredients (herbs, minerals and wax), justifying their grouping, the crossover could also be an early acknowledgement that in order to heal the body, you needed to care for the heart and mind as well.

I discovered this connection on an art and apothecary tour, an experience that delves beneath the city’s grandeur and reveals that the past is rarely as far away as we think. It’s one of the many Tuscan experiences Villa San Michele curates for its guests.

Part of the Belmond collection, Villa San Michele is a hotel worth lusting over. Found in the Fiesole hills, where the Etruscans settled long before the Romans took an interest in founding Florence, the property was built as a monastery in the 15th century and remains wondrously atmospheric. There’s a lofty stone and terracotta facade designed by the School of Michelangelo, an ornate church-turned-reception, artfully-faded frescoes, cavernous fireplaces and vaulted ceilings. And sweeping past the infinity pool and terraced gardens (bedecked with sculptures, olive groves and a 400-year-old wisteria), you reach a woodland path that leads to Montececeri Park, where Leonardo Da Vinci is said to have experimented with flight.

Villa San Michele feels so opulent that it doesn’t seem entirely real. Its covered cloisters and stone archways instead become a stage, a fantasy brought to life, and you feel infinitely more elegant by simply swanning through the hotel’s halls. Thankfully, playing the part of a travelling glamazon is incredibly easy. You can lounge in your suite, unwind with yoga in the sun, or sip a Negroni in the bar (a fitting choice given that the cocktail was first mixed in Florence), before floating through to La Loggia restaurant. Every culinary detail here has been carefully considered, right down to the olive oil, which was sourced from a different farm every night of my stay. And while the fare is divine (a display of local terroir and sustainable producers), it’s the view that captivates. Far below you, nestled in the Arno Valley, Florence twinkles.

Given its position, it’s little wonder Villa San Michele is besotted with the city and committed to showcasing its treasures. Crockery hails from Richard Ginori (who made ceramics for the Medicis), biscotti is from Antonio Mattei (to look like a local, dip your biscuit into a glass of Vin Santo), and their excursions transform Florence into your playground. You can savour delights on a private food tour, spend an afternoon with craftspeople, raft down the Arno River, or explore the world of apothecaries - my own experience ending in Santa Maria Novella 1221, Europe’s oldest monastic pharmacy.

The Dominican friars who founded Santa Maria Novella convent in 1221 (hence the name) quickly developed a fascination with herbs, and went on to create cures and cosmetics, the descendants of which can be purchased in their Enlightenment Era store, still found in the convent’s cloisters. Santa Maria Novella’s rose water (made from a recipe that has changed little since 1381) may be one of their oldest creations, but the Angels of Florence scent is possibly the loveliest. With hints of rosemary and peach, it honours those who came to save the city’s art and architecture after the Arno flooded in 1966.

Returning to Villa San Michele, my bags filled with perfume and biscotti, I felt as if I’d come back from a jaunt behind the scenes. Awash with history, it’s difficult to fully know Florence, and perhaps the mystique is part of the allure. But when it comes to brilliant introductions, no one does it with quite as much panache as Villa San Michele.

Earthly Delights

A cheese-and-cider pilgrimage to Asturias.

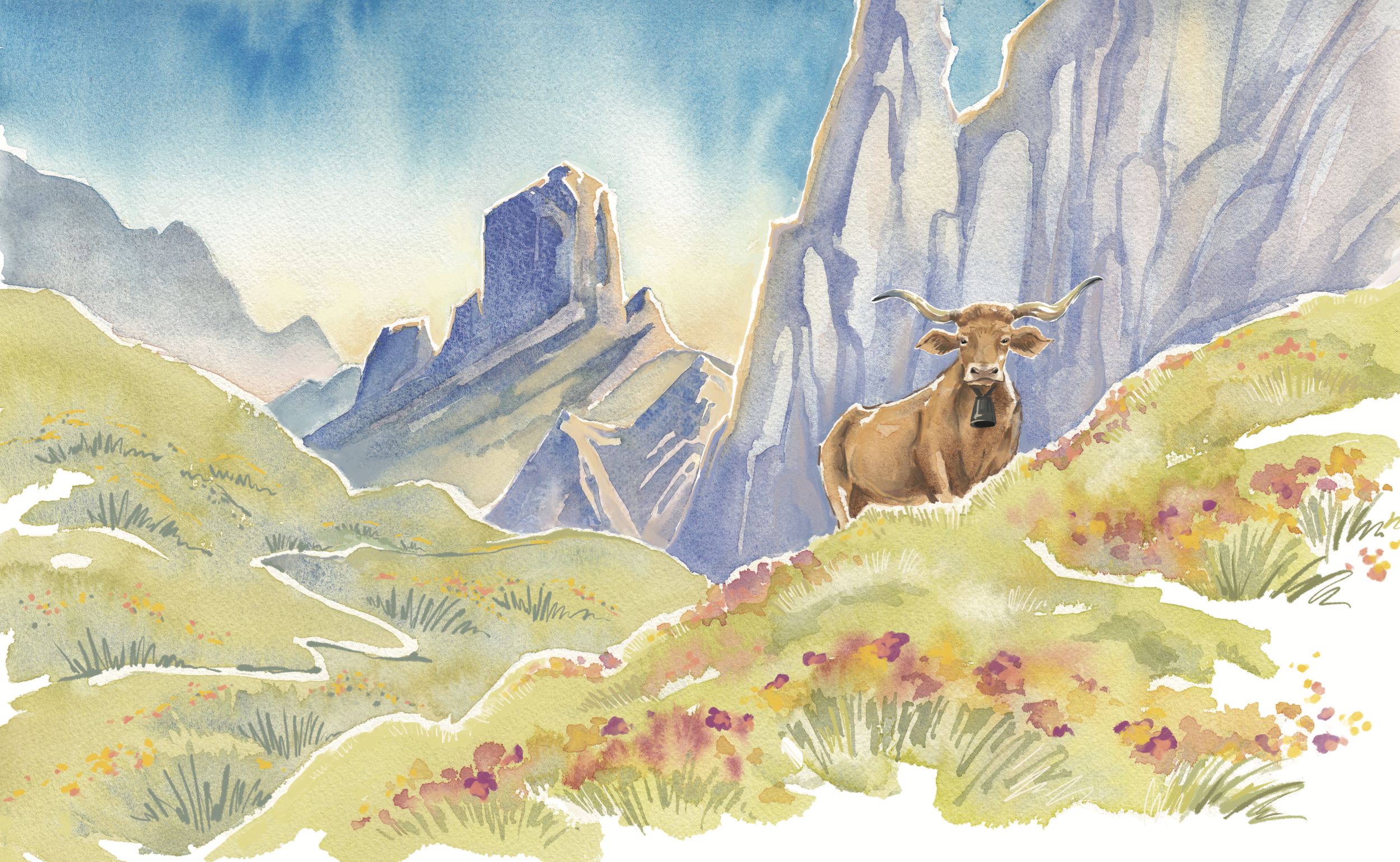

An extract from the Spain magazine - Words by Karyn Noble & Illustrations by Piera Cirefice

Years before I visited Spain, I sat in a hot and humid lounge room in my then home of Australia, glued to a documentary by Master of Cheese Will Studd called Cheese Slices. In one episode, he declared that most of Spain’s hundreds-odd cheeses were unknown to the rest of the world - before travelling through the lush Picos de Europa mountains, via tiny villages, to misty caves where he went deep within to taste one of the best and rarest cheeses of Asturias.

Fast forward to almost a decade later - 2021 - and I’m in the very same spot, visiting the principality of Asturias for the World Cheese Awards. Admittedly, when I was watching Cheese Slices and shouting, “That bit! That’s the part of Spain I want to visit”, I didn’t quite foresee that I would eventually be here in such glorious circumstances. While many outdoor enthusiasts are attracted to Asturias for the hiking, unspoilt beaches, medieval ports and sailing villages, I spend a good part of my trip underground, inhaling pungent, award-winning cheese. Daylight can be overrated, you know.

Other parts of Spain may bristle at my assertion that ‘the best cheese’ is found here, but there’s no getting around the fact that there are more varieties of cheese produced in Asturias than in any other part of the country (no-one can agree on exact figures, but it’s believed to be in the realm of 300). Cabrales and Gamonéu - both made from cow, sheep and goat milk - are just two of eastern Asturias’ PDO-status blue cheeses that mature in the region’s 5.5-kilometre maze of caves.

My first encounter with a cheese cave feels a bit like going to see Batman in his Batcave. I drive up the misty, winding hills of the Picos de Europa to increasingly dramatic sea-and-mountain views, until my car comes to a gravelly halt beside a precipice and a square entrance into a mountain. The cave looks suitably dark and mysterious; there’s zero signage and just a wooden gate slightly ajar to indicate that there might be something welcoming inside. And while there are some bats deep within, the musty aroma emanating from the chilly, limestone interior is unmistakably cheesy. I don’t need my eyes to adjust to the dim lighting to know that there are rounds of Gamonéu ageing here, lined up in what look like wooden bookcases for their two-month stay of maturation. Gamonéu is one of the oldest varieties of cheese in Asturias, and it’s a lightly smoked blue that benefits from the unique topography of the karst terrain, and a microclimate shaped by sea mist and fog.

The magic continues on another mountainous journey to one of the principality’s best restaurants, Casa Marcial, in the remote village of La Salzar. This is the two-Michelin-starred domain of chefs Nacho and Esther Manzano, a brother-and-sister team who grew up (alongside siblings and co-workers Sandra and Olga) in this two-storey, brick-and- wood building that is now an homage to Asturian nature and gastronomy. Inspired by their mother’s cooking, the duo restore traditional recipes to meet the modern palate, with their creative and intuitive genius on display in the multiple tasting courses.

Given the abundance of cheese varieties in Asturias, I ask Nacho if he could narrow down his top five favourites for anyone visiting the region for the first time. He deliberates at great length and, thinking that perhaps three or four might be easier to choose, I attempt to nudge him along - but he is determined to give me five, clearly delighted with the challenge: “Gamonéu, Cabrales, Beyos, Afuega’l Pitu and Varé,” he eventually says.

I’d tried Cabrales, his second choice, at a cave I’d explored earlier that day. While I loved its creaminess and jolt of intensity, it’s one of the world’s most pungent (and expensive) cheeses and not for the blue-cheese averse; I’ve known a food-judging companion to liken it to “licking a car battery”, which is a fair comment. It’s not until I reach the elegant Asturian capital of Oviedo that I start to develop a greater appreciation for it. At another of Esther and Nacho’s creations, Gloria, a casa de comidas (a Spanish restaurant known for traditional food at affordable prices), I try a dish Nacho invented at the age of 13: the maize tortu with caramelised onions and Cabrales cheese. A tortu is an Asturian word for deep-fried flatbread, and this is not an Instagrammable dish by any means: a thick, oozy beige spilling from little vessels of bread that look like taco cups. The taste is another matter entirely. I am transfixed by the complexity and synchronicity of the contrasting textures and flavours; the sweetness of the onions countering the creamy sharpness of the Cabrales, the fried bread distracting and absorbing. While atortu is now relatively common in Asturias, Nacho has elevated what sounds like a dense dish to light fluffiness, and I find myself craving a hangover as an excuse to keep indulging in this most addictive of comfort foods.

Fortunately, ‘Cider Boulevard’ beckoned. And how. Along this laneway of sidrerías (cider houses) on Ovideo’s Calle Gascona, visitors can enjoy their drinks escanciado (poured theatrically into a glass from overhead). Cider is an important part of Asturian history. It is home to almost 500 varieties of apples, 22 of which are approved for cider use; look for the green Sidra de Asturias Designation of Origin label on the bottles (more than 40-million of them are produced annually in the principality’s 80 cider mills).

My baptism by elevated-cider-stream fire comes at El Ferroviario, the very first cider house on Calle Gascona, which serves libations from each of Asturias’ four cider-producing regions. Don’t be offended if you think your tipple is on the small side; if it’s poured from a height it should only fill about a quarter of your glass - this enhances the bubbles, froth and aromas, giving it the perfect amount of oxygen to be imbibed in just one sip. Rest assured that many sips were had on Cider Boulevard.

But if there’s one drink that encapsulates my cheese expedition to Asturias, it’s a liqueur served in Las Arenas, at the foothills of the Picos de Europa, one sunny lunchtime. It arrives in a white bottle with the word ‘penicillium’ written on it against an image of the Naranjo de Bulnes limestone peak and various wildflowers. It is presented enigmatically by my host at tapas bar La Cabraliega, and the bottle gives me no clues whatsoever. The intrigue continues as the liquid is poured into a shot glass, the palest of lemon-copper in shade. I wonder if it’s a kind of limoncello when I feel its icy coldness, but then the aroma leaves no doubt. “It’s a Cabrales cheese liqueur,” confirms my host. “Do you like it?” Much like Cabrales cheese itself, it divides the table. The musky, cave-like aroma is nothing at all like the taste, which is surprisingly refreshing, with notes of white chocolate, butter and toast. It seems Asturias is a principality of many surprises, especially its food and drink - and occasionally both at once.

Conversations With Friends

An Irish road trip curated by the kindest of strangers.

Words by Liz Schaffer & Photographs by Orlando Gili

Sharing a story from our Ireland magazine.

My first night in Belfast was a blur. Not only because we revelled in pubs and the weather gods put on a show, but because I realised - three-whiskeys-in as musicians let loose in Madden’s Bar - precisely how brilliant an Irish heart-to-heart can be. Chatting at the bar, or while perched at the end of tables, I was struck by the openness, pride and sense that the conversations you have here might just change the way you see the world. Failing that, they’ll at least introduce you to someone fabulous - a friend with a Sligo bathhouse perhaps?

While this was a lovely discovery, it also came as a relief. Having been told time and again that Ireland is a nation of storytellers, I’d decided to bring a photo-taking-friend along on a road trip, and keep our itinerary deliberately vague. Hotels were booked, and a few sites deemed unmissable, but I was keen to leave the majority of the route up to those we met along the way.

My plan kicked in the moment we checked in to the riot of genteel eccentricity that is The Harrison Chambers of Distinction, a 16-room boutique hotel with a vibrant bohemian heart. Found in a converted Victorian merchant’s residence, across the road from the Botanic Gardens, each spacious room boasts a unique design inspired by a beloved personality from Northern Ireland - think C.S. Lewis, Jonathan Swift and Hans Sloane. My suite (named for the latter) was bedecked with a bay window and clawfoot tub, flashes of velvet, ornate cornices and swoon-inducing vintage furnishings sourced from across the globe. The artfully curated interiors are the work of owner Melanie Harrison, who adores her city. Among her many recommendations were Books Paper Scissors (if you’re after something penned by a Belfast native, this is where you shop) and the brilliantly-titled Crown Liquor Saloon for the first of many libations.

Things became a touch more debauched at The Duke of York, where we caroused among flower pots and fairy lights, and The Spaniard, where we crossed paths with photographer Olin Brannigan, who has passed many rain-soaked nights capturing Ireland’s Megalithic monuments. Not only did he confirm that our geological respects must be paid to The Burren National Park, but that a seaweed bath was vital - and he knew just the person to speak to about that.

So, the next day we drove across Antrim, paused for brunch at Third Day Coffee (their French toast is worth planning a trip around), swooned over Fermanagh’s Florence Court House, and tumbled from the car at Kilcullen’s Seaweed Baths, where Olin’s friend Cain was waiting.

Cain Kilcullen’s family have run these baths overlooking Enniscrone Beach for four generations (it opened the year the Titanic sank), and the process hasn’t changed much over the decades. You begin in a vintage steam box, before soaking in a tub with fresh, hand-harvested seaweed, and end with a cold salt water shower. Packed with iodine, magnesium, zinc and omega, the seaweed was a tonic that soothed my road-weary body and left me more energised than I’d been for weeks.

Cain’s love for the coast began early. He begged the surfers at Easkey Beach to teach him as a child, and has surfed every day since. For him, on a good day, the waves off Ireland’s west coast are some of the world’s best; but as blue sky can be elusive and winter temperatures brutal, surfing is a ritual for the devoted. Noting my hesitance to dive in, Cain instead suggested we make the most of the summer light and drive to Downpatrick Head.

It’s hard to describe the thrill that comes with a seemingly endless summer evening. The warmth, the hues, the suspicion that the landscape is putting on this otherworldly show just for you, makes you wonder if some strange magic is at play. Indeed, walking over the headland’s spongy moss-and-broom mounds towards the Dún Briste sea stack - the sky candy-floss pink and the waves blending with the mellifluous call of gulls - I followed what I assumed was a stone path being slowly devoured by the earth. Turns out it was the remnants of the Éire 64 sign, which the community had quietly restored. Around 80 of these markers were carved across the coastline during the Second World War to let pilots know they were flying over neutral Ireland. In this part of the world, you literally stumble over history.

We spent the night at Ballina’s Ice House Hotel & Spa, which is perched above the salmon-rich River Moy, not far from the Sligo Way walking route. It began life as an ice store (in 1836), and while the antiques-adorned Heritage Rooms honour its past, the Riverside Suites are decorous, contemporary affairs. There’s an abundance of natural light, stonework inspired by the drama of the Wild Atlantic Way, beds that envelop you, and immense windows ideal for taking in uninterrupted views of the swan-studded water. And then there’s the Chill Spa - a sleek and restorative oasis if ever there was one. Having given myself the task of indulging in as many seaweed baths as possible, I sank into one of the spa’s outdoor tubs the following morning and set about soaking up those nutrients, sustained by tea, sorbet and the promise of breakfast as I watched the clouds dance by.

The next leg of our odyssey delivered us to West Cork, although a requisite hike through The Burren’s lunar-esque, limestone terrain saw us arrive at Dunmore House under cover of darkness. And while I felt at home the minute convivial co-owner Carol Barrett swept me up in a fireside conversation, there’s a lot to be said for allowing this family-run boutique hotel to reveal itself with the rising sun, when the panoramic view over Clonakilty Bay (visible from every bedroom) is at its most spectacular.

An early morning wander through the hotel’s rolling grounds revealed a wildflower paddock, private beach, beckoning hammocks, sculptures by Moss Gaynor and a picturesque kitchen garden dotted with contented chickens. Standing among the courgettes and flowering sweet peas, I felt myself getting a little lost in the seascape, and watched as bursts of sunlight transformed the waves from moody greys to dazzling teals. For Antonia, one of Dunmore’s kitchen gardeners, the water is magnificent. “If you turn up in a bad mood, it will absolutely ground you. Some days it’s like glass, other times it roars, but it is always hypnotising.” With a backdrop like this, it’s little wonder fare from the hotel’s Adrift Restaurant is so delicious - or that Dunmore’s palette, decor and extensive art collection are elegant odes to the sea.

On hearing that we were bound for West Cork, writer and editor Kristin Jensen (who founded Blasta Books, which publishes quarterly cookbooks, and Scoop, an Irish food magazine) introduced us to Sally Barnes, the force of nature behind Woodcock Smokery. Sally is a pioneer, renowned for helping to bring Ireland’s artisan food traditions to the fore. She has smoke-cured fish by hand for four decades, her journey beginning when her then-husband came home from a weekend of rod fishing with five trout, each weighing more than four pounds. “I was furious,” says Sally, “because we had two small babies, and I thought who is going to eat these? I haven’t got a freezer, I haven’t got any way of conserving them! But being cross started a conversation about what people did before - how they conserved fish in times of plenty.”

Through experimentation, Sally found her way to salt-curing and smoke-drying, going on to supply the community and develop a unique recipe. Today, she runs courses with Max Jones of Up There The Last - a traditional food conservation project that aims to maintain food heritage and knowledge through immersive experiences. We’d met Max earlier that day beside Castletownshend pier as fishermen readied their rowboats, and he’d arrived bearing snacks: homemade brown bread slathered in butter and topped with Sally’s salmon, which he described as “truly wild”.

For Max, food is everything. He believes in the importance of connection, recipe- sharing and experimentation. “With the Woodcock Smokery workshops, we’re essentially teaching people what wild means,” he explains. “Real food, the best stuff, if you chase it back to source, is about the lives of people, the makers. They’ve got all of their sustainability absolutely dialled in because they’re using traditional techniques that pre-date industry ... The best way for knowledge like that to not disappear is to open Sally’s brain to everybody.”

A little later, tucking into a makeshift picnic outside Kinsale’s tangerine-hued Bulman Bar as kids leapt from the sea wall, I thought about Max’s words. Everyone we’d met had been so willing to share their insights, and to champion the projects, people and places that meant something to them. In fact, we’d found out about our lunch spot after striking up a conversation in an Innishannon pub with a dairy farmer who swims around the bay’s island every morning.

There’s something special about Irish waters, they have a way of beguiling you. Perhaps the fact they’re prone to being so terrifying wild means that when things are calm, you can’t look away - or think about anything but the scene before you. I sensed this outside The Bulman, and again in Ardmore while wandering the town’s Cliff Walk, found near the swish, art-centric Cliff House Hotel (one of the few planned stops on our trip). This is not a lengthy route, but it’s one that will fire up your imagination as you pass crumbling cathedrals, shipwrecks and Napoleonic lookouts being slowly consumed by the land and sea. When you finally return to Ardmore’s harbour and spy intrepid swimmers wading out into the millpond blue, you find that everything has slowed; your breath, thoughts, even the late summer sun seems to be taking its time to dip below the horizon, leaving a melange of lilac and magenta in its wake.

I could have stayed by that seascape forever. But alas, even the most glorious odysseys must draw to a close. Our last hedonistic evening unfolded on the streets of Dublin, both of us aware that road trips that begin with serendipitous pub hopping, should also end that way.

So, that’s how we found ourselves in The Cobblestone, ‘a drinking pub with a music problem’. This traditional Irish music bar is overseen by Tom Mulligan, who comes from a long line of musicians. His songwriter son was behind the bar, and his daughters both play the fiddle - one with her left hand and one with her right. Surrounded by chatter and song, I couldn’t remember who first told us about Tom. All I knew, watching him play his recorder by The Cobblestone window, was that I rarely felt this content. While the music certainly made spirits soar, my cheer was clearly the culmination of a week on the Irish road, and the warmth, beauty and chance encounters that came with it.

Leaving Ireland is hard. The landscapes inspire, history follows you everywhere, and if you strike up a conversation, it’s likely you’ll embark on a journey that’s far more wondrous than the one you had planned. Ireland is a place that will have you talking - and it’s best to go along for the ride.

For more stories from the island of Ireland, check out the magazine.

Stone and Timber

The allure of old spaces and grand designs.

Words by Jen Harrison Bunning & Photographs by Tom Bunning

Think of a self-catering holiday and where does your imagination take you? Perhaps it’s to a shepherd’s hut, pod or luxury yurt? All very appealing prospects, but if you’re fortunate enough to be acquainted with the Landmark Trust, then your thoughts might head for more ancient dwellings. You may find yourself torn between a 19th century railway station in Staffordshire, a water tower in Norfolk or one of the few Jacobean houses in Spitalfields that survived the Great Fire of London. Maybe a converted pigsty in Yorkshire or a castle keep in the Devon estuary will take your fancy. Or you may settle on the great hall of a vanished manor house in a honey-stoned Somerset village.

The Landmark Trust is an architectural conservation charity with a simple mission: to rescue ‘historic buildings that are at risk and give them a new and secure future.’ Founded in 1965, in the midst of Beeching’s decimation of the railways and the country-wide demolition of crumbling great houses, the Trust began when Sir John Smith, a young London MP with a passion for architecture, and his wife, Christian, came up with what was, at the time, a fairly madcap plan. One to save buildings of domestic or industrial heritage that were too difficult, too remote, too small or not historically significant enough for the National Trust or the Ministry of Works to take on. The couple’s aim was to preserve these properties, in their words, “not as museum pieces, to be peeked at over a rope, but as living places which people could inhabit as their own for short spells.”

And that is what the Landmark Trust has been steadily doing for the last 50-odd years. From its first mission to save a Victorian cottage in Cardiganshire, there are now some 200 properties in the Landmark collection (mostly in the UK but with a handful on the continent), each sensitively restored to reflect its unique and fascinating past. It was one of their most challenging restoration projects that we were off to experience for ourselves; The Old Hall in Croscombe, deep in the heart of Somerset.

The village of Croscombe lies betwixt Wells and Shepton Mallet where the River Sheppey slices through the Mendip Hills. It looks wonderfully sleepy with its abundance of pretty stone cottages and houses dating back to Jacobean, Tudor and medieval times, their gardens teeming with scented jasmine, roses and wisteria.

The Old Hall can be found tucked away behind the church, up a lane bound for the hills. Originally part of a baronial house built in around 1420, what remains stands in a tranquil walled garden with clambering roses, apple trees and a tumbledown graveyard. Once part of a home built for newly-weds, the vagaries of succession meant it passed between various wealthy families over several centuries, slowly falling into disrepair. A wing was lost, a chamber collapsed, but the Hall itself continued to be used as a meeting room for manorial business and later by a congregation of Baptists, who can be credited with first saving the building when they bought it in around 1730. Whilst they made permanent alterations to accommodate the chapel, they also took care of the property, re-plastering, painting and repairing the walls and ceiling. After the Second World War the congregation dwindled and the chapel passed into the hands of the church’s District Association before being rescued by the Trust in the 70s and undergoing a huge restoration which involved unblocking doors, relaying floors, uncovering plasterwork, salvaging medieval windows and even covering over a baptismal well.

At the heart of the building is the hall itself, with its show-stopper of a Victorian roof. Creak open the door and your eyes are immediately drawn up to marvel at the five oak arched brace trusses vaulting overhead. Covered by a false ceiling for hundreds of years, the oak has never been stained and its natural rich tones combine with ochre-tinted rough plaster walls, a red quarry tiled floor and late summer light streaming in through giant windows to give a wonderfully warm and welcoming effect.

At the east end of the hall, you step through to what has, in its various incarnations, been a buttery, vestry and perhaps once a stable and school house too. It is now a simple but well-equipped kitchen with a pale grey flagstone floor and handsome furniture. At its centre is a hearth with an ancient, blackened stove that no longer fires but looks most pleasing - and there’s a modern galley with all the essentials tucked around it.

Up the winding staircase are two modest bedrooms, a deliciously dark double tucked at the back and a triple with a sweet shuttered window and views of the church to the front, both with original fireplaces, hand-printed curtains and charming lamps converted from old stoneware.

Despite the historic nature of the Hall and its delicate restoration, its spaces are designed for living in and, whilst the furnishings are attractive and of high quality, nothing here is too good for daily use. This is interior design that will never go out of style, all fashioned to complement the glorious old bones of the building. And this home-from-home appeal is no accident. As Landmark’s Furnishing Manager John Evetts wrote for an issue of Listed Heritage magazine, “I hope that visitors bring something of their own to the buildings for the few days in which they inhabit [them] ... so I like to leave empty spaces in which they can position them.” Pegs await shopping bags, garments and dog leads, jugs await flowers and racks await boots.

It’s true that The Old Hall lacks what some might consider to be modern-day essentials: there’s no WiFi or television and little reception, but most fun and relaxation usually happens when you cut yourself off from technology for a short while and appreciate what’s right in front of you. If you were desperate you could easily walk up the hill or down to the pub to get a signal, but why would you? (Unless it’s just an excuse to have a top-notch basket of scampi at The George Inn.)

On our last evening, carrying cameras, notebooks and a bottle of rosé, we tramped up the hill to toast the end of a dreamy long weekend. Settling on a ridge overlooking the village, we watched the day fade into silvery dusk and agreed that this was England at her most seductive - wondering, not for the first time, just why we were heading back to London in the morning.

Given the enormous range of self-catering properties available, why choose a Landmark? Well, there’s not enough space within these pages for a full rhapsody, but you’re unlikely to find such a range of quirky and interesting places to stay on offer anywhere else. And every stay makes a difference to the Trust, so you’ll have an added feel-good glow from knowing you’re helping to rescue historical buildings for future generations.

Go with family or friends to a castle or manor house and spend a week feasting at long tables, stomping about in the mud and playing furious games of Scrabble. Go and explore a town or city with a weaver’s cottage or parsonage as your base. Go à deux to a bolthole for a romantic weekend or, given how reasonable the rates are, venture alone to a medieval chapel for a dose of solitude.

John and Christian’s original aim was to rescue what they called “unfashionable” properties, but as we gallop through the 21st century with all of its bells and whistles and throw-away consumables, the sort of pared-back, comfortable stay you’ll experience at a Landmark has unwittingly become on trend. At least to those of us who seek simplicity, appreciate well-made things, and take pleasure in the unchanging nature and quiet beauty of ancient buildings and their surroundings.

This story first appeared in our England magazine, which you can purchase here.

Oaxaca's Flowers

Meeting the artisans of Mexico’s Oaxaca.

Photo Essay by Jimena Peck - first published in the Mexico magazine.

In the mountain village of Teotitlán del Valle, nestled in the shadow of Oaxaca’s cascading sierra, candlemakers have long held an important community role; their meticulously crafted wares forming the heart of traditional ceremonies, religious practices and daily celebrations. Today, the candles continue to shine brightly, illuminating the small Oaxacan town’s future. These are no ordinary votives.

The velas de concha - ‘shell’ candles unique to the village - have cast their soft white glow over the residents’ homes and rituals for years. During my visit to Oaxaca’s lush central valley, I met Viviana, the matriarch of a clan of artisans, who has been a candlemaker in Teotitlán for more than 50 years. Now, against the odds, her sons and daughters-in-law take part in the family tradition; a practice that has anchored them for four generations.

These candles have always been highly valued goods in Oaxaca, prized for their beauty and intricacy - some can rise above two metres tall and feature hundreds of detailed decorations. The process is equally fascinating, combining deft technical skill with finesse and the special touch that only a life-long Teotitlán candlemaker can bring.

The candle’s skeleton - or basic structure - is made as the wick hangs from a large circular ring attached to the high ceiling of Viviana’s patio. They pour hot wax over the wick, increasing the candle’s size and diameter layer by layer in a process called dripping.

The delicate shell or flower-like adornments that give the candles their name are the most creative part of the process. This is when Viviana and her daughters-in-law get expressive, enjoying the aesthetic challenges each candle presents. They carefully craft wax flowers in wooden moulds which they dip in hot wax, cool in a pail of water, and then cut with scissors, forming the blooms’ petals. Next, they wrap a mylar ribbon around the candle’s skeleton, insert a wire into the wax flower’s centre, gently heat each wire over a flame, and attach it to the candle. This is done again and again, until the candle bursts with lovely, scalloped curves. Each flower is unique, its contours brought to life by the soft light filtering through the workshop’s window.

In Teotitlán del Valle, time doesn’t stand still - the bustling Oaxacan capital lies just down the modern highway and the noise of cars, tiny televisions and smartphones buzzes through the village. What’s remarkable about Teotitlán, though, is how its rich, meaningful traditions are kept alive, seamlessly fitting into daily life in modern Mexico. It was spellbinding to watch Viviana and her family craft velas de concha, each painstaking detail resulting in a work of exquisite artistry. For them, the candles flicker warmly, lighting their path as they make their livelihood into an art form.

Summer Wonderland

Off piste at La Plange.

Words & Text by Beth Squire

The ten alpine villages of La Plagne have long been adored for all they offer in winter - from ski runs down crisp white slopes to the chance to zip along the only bobsleigh track in Europe. It is an undisputed winter wonderland, all snow-dusted pines and evenings full of mulled wine and tartiflette. So I was surprised to discover just how much there is to do in summer, when La Plagne is a region transformed. There are activities to suit all ages and abilities, from gentle strolls through the mountains to a via ferrata, which isn’t for the faint-hearted - although the adrenaline-fuelled clamber is more than justified by the view of Mont Blanc, regal upon the horizon.

It’s impossible to visit this ski area in summer and not succumb to itchy feet - for the view beyond the window, a kaleidoscopic display of green alpine perfection, beckons to all. So you hike, cycle, bask, canyon, geocache, horse ride or head for the water, depending on your inclination. Never one to refuse a spot of rafting, I leapt at the chance to dive in and paddle through the Isère Valley. Little did I know though that the expedition ended with a 30 foot cliff jump; plunging feet first into freezing water definitely sets your heart racing.

While there are only a few roads that weave between the snow-topped peaks of La Plagne, everything is remarkably accessible. You can wake up in your village, hop on a bike, and be in the mountains in no time, enjoying a picnic breakfast beneath the early morning sun. These trails - hidden under powdery snow come winter - offer secluded views impossible to spy from the road, or when flying devil-may-care down a black piste. All the more incentive to grab a bike and break a sweat with some pedalling.